When I wrote my first post on this blog about a year and a half ago, I only had access to religious data at a district-by-district level for Punjab (and also Bengal). When I wrote my post on Kashmir, I switched to using sub-district (or tehsil) data, which is more detailed. Since then, all of my posts on Partition have used that more detailed data from the 1931 Census. I decided to revise the Punjab map using the tehsil data. I won’t rewrite the whole post here though I encourage you to read it here. Instead I’ll compare the original map to the new one, and discuss a few features that the increased resolution reveals.

Apart from the obvious improvement in quality, and my addition of much of the North-West Frontier Province to the second map, there are a few details worth commenting on, though obviously the overall picture remains largely unchanged. First there was an overwhelmingly Muslim pocket due south of Delhi, far from any other Muslim majority area. Second, the increased detail really emphasizes the concentration of Sikhs in the southern half of what is now the Indian state of Punjab. The northern half of Indian Punjab was very mixed, with large Hindu, Muslim, and Sikh populations. Third, Amritsar and Tarn Taran tehsils, which are the Sikh-plurality (blue) tehsils directly in the middle of the province, were mostly surrounded by Muslim-majority or Muslim-plurality tehsils. This will be relevant when we look more closely at the partition lines later in the post. Finally, I noticed the Sikh-heavy area west of Amritsar centered on Lyallpur (modern-day Faisalabad). This part of Punjab was the focus of a major British plan to irrigate previously arid parts of Punjab and turn them into agricultural centers. Often, Sikhs migrated to these so-called canal colonies, where they were given plots of land to farm. The west-central part of Punjab, where most of these colonies were, tended to be Muslim-majority, but with a larger Sikh than Hindu population. Farther west, the Muslim majority became more pronounced, but the minority population was mostly Hindu. Below is a map of the non-Muslim Punjab population, to reveal the Hindu/Sikh distribution (the “Sikh” category actually includes all other religions, but the Sikhs made up the overwhelming majority of the non-Muslim, non-Hindu population).

I adjusted the opacity so that the colors look more faded as the non-Muslim share of the population decreases. As you can see, the Sikhs are mostly concentrated in the central Punjab. Hindus are much more numerous than Sikhs in the south and west of the state. I think this may be due to the canal colonies, which were located in the west-central Punjab and were a major magnet for Sikh migrants in the early 1900s. Farther west and south, the main minority is presumably the ten or fifteen percent of the original Hindu population who didn’t convert to Islam during the seven centuries or so of Muslim rule over western Punjab.

In this post, I experimented with a few different ways of presenting the data. The map below, requested by Vikram, a commenter, is a map depicting the Muslim vs. non-Muslim breakdown, which was the basis of the British partition lines.

Now here is the same map, but with the partition line drawn in.

Here we see clearly that the Radcliffe Line (the official name of the border between India and Pakistan) in Punjab was very favorable to India, as I noted in my original post. Not a single non-Muslim-majority tehsil or princely state ended up in Pakistan, while nine Muslim-majority tehsils or states ended up in India. Furthermore, seven of these were contiguous or near-contiguous with Pakistan. Here is the same map with the nine Muslim-majority tehsils given to India highlighted.

The seven Muslim tehsils near the Pakistan border plus the two non-Muslim tehsils they surround, Tarn Taran and Amritsar, had an overall religious profile of 52.0 percent Muslim, 27.3 percent Sikh, 18.4 percent Hindu, and 2.1 percent Christian. Therefore, theoretically, the concept of “two nations” would have been better served if the whole block had gone to Pakistan. That way, only four tehsils would have been “stranded” on the wrong side of the line, two per country. That still wouldn’t have been a satisfying solution to me though because the goal of Partition should have been to minimize displacement of people, not create a solution that was abstractly “fair” to both India and Pakistan. I think a better option would have been to give as much of this Muslim-majority block as possible to Pakistan while keeping Tarn Taran and Amritsar in India. There would have been two obvious options for achieving this goal. One would have been for Kapurthala state, southeast of Tarn Taran and Amritsar to accede to India while the remainder of the Muslim tehsils went to Pakistan. Alternatively, Gurdaspur and Batala tehsils, just to the north of Amritsar, could have remained with India while the other Muslim-majority tehsils and Kapurthala state went to Pakistan.

I judged which of these would have been better by assuming that all “stranded” Sikhs and Hindus would have moved to India, all Muslims would have moved to Pakistan, and Christians would have stayed put, as that is how Partition played out in general. Then I calculated how many refugees would have been expected under each scenario. The first scenario, Partition as it actually occurred, resulted in about 1,359,000 refugees from this pocket of Muslim-majority areas given to India. The second scenario, Kapurthala staying with India, would have generated 1,167,000 refugees and would have looked like this:

The third would have involved Gurdaspur and Batala staying with India, would have resulted in 1,177,000 refugees, and would look like this:

A possible fourth option would have been for the whole area to go to Pakistan. That would have resulted in 1,195,000 refugees and look like this:

Obviously, if we reject the rules set up by the British and think outside the box, there are other possible outcomes that could have reduced or eliminated refugees. Some such possibilities include a multi-religious neutral zone in central Punjab, an independent and united Punjab, or no Partition of India at all. However, accepting the rules as defined by the British, the second option of Kapurthala going to India would have had the fewest refugees. Unsurprisingly, the British chose the one that created the most refugees. It is quite possible that the British wanted to make sure that the Sikhs, who were left in a very bad situation by Partition, would not be forced to abandon Amritsar, their holy city. Thus all the Muslim tehsils around Amritsar were given to India to make Amritsar more defensible and less exposed. It isn’t obvious to me though that the border in option two above was dramatically less defensible. Amritsar was more exposed, but any border through that part of Punjab would be difficult to defend given the flat topography. And the British left Pakistan divided in two and separated by the length of India, presumably a much greater obstacle to defensibility than a zigzag in the Punjab border. It should also be noted that the actual border drawn in that exact region proved impossible to defend for Pakistan in the 1965 war, when India invaded and ended up on the outskirts of Lahore by the time a cease-fire was declared.

Perhaps the British were willing to give India a favorable deal in Punjab (and as commenters have pointed out, in Bengal too) as a way of convincing the Congress leadership to accept Pakistan’s creation. I think that the main reason the British supported Pakistan’s creation is that it kept the most strategically valuable parts of British India in somewhat friendly hands. The North-West Frontier Province, parts of Kashmir (which the British expected to go to Pakistan), and perhaps Balochistan were strategic in the Cold War with the Soviet Union, which was already underway by 1947. As long as those territories ended up in Pakistan, the British probably weren’t too picky about what else ended up where. They may have promised and delivered India a favorable deal to ensure that India’s leadership wouldn’t get difficult and prevent the British from leaving the subcontinent quickly and unobtrusively. The British also wanted to ensure that India’s leadership wouldn’t drag its heals on recognizing Pakistan’s legitimacy (India voted in favor of Pakistan’s admission to the UN, Afghanistan was the only country opposed). So maybe the generous amount of land given to India in Punjab and the strategic headwaters in Bengal were meant to quietly grease the wheels for the British Empire’s withdrawal from South Asia and Pakistan’s entrance onto the world stage.

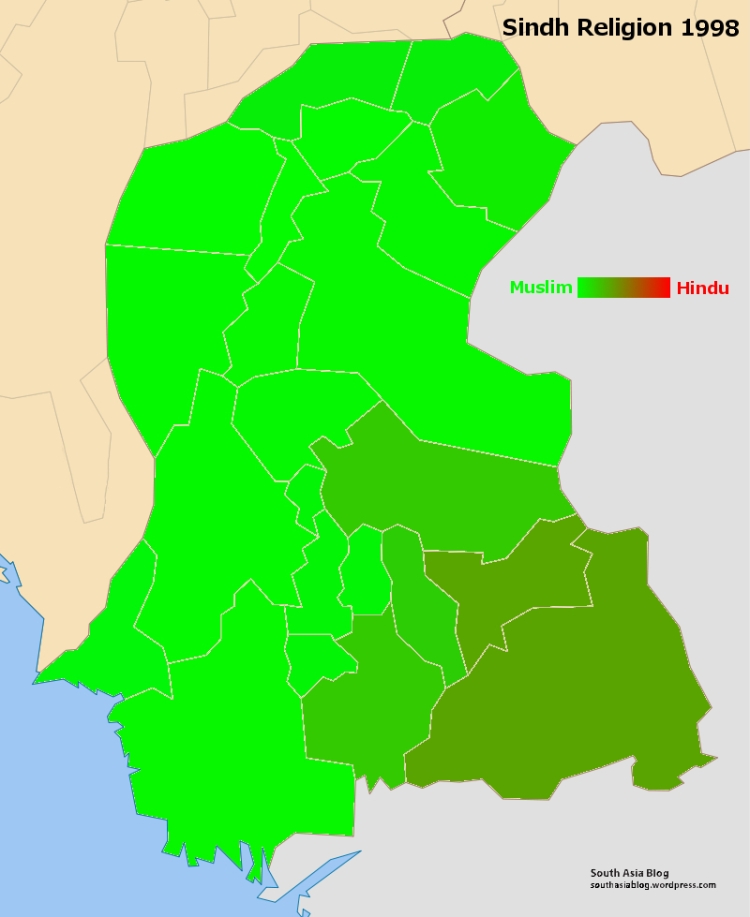

Finally the original goal of this project was to examine how Partition affected the religious demographics of Punjab, so I will post the original map with the 1931 populations, and the map with 2001 (India) and 1998 (Pakistan) populations so you can see how Partition changed Punjab forever. It is especially worth noting the change in the Muslim-majority teshils that remained in India, which must have lost a majority of their population in 1947, and the narrow Muslim-majority tehsils in Pakistan, which lost just a bit less than half.